Progressive Research Program

Psychotherapy researchers Bruce Wampold and Zac Imel applied Hungarian philosopher Imre Lakatos' philosophy of science in psychotherapy as a way to evaluate and compare competing scientific research programs. Lakatos' theories provide a framework for psychotherapy research in their robust second edition of The Great Psychotherapy Debate, which informs our approach to research with the Outdoor Therapy Centre.

A research program consists of a hard core of fundamental assumptions and a protective belt linking these ideas to the wider world of psychotherapy practice and the helping professionals. These ideas can be modified or abandoned without undermining the core, but adjust themselves to protect the fundamental assumptions. Changes to a protective belt are welcome, and encouraged, but these changes still prevent the falsification of our core assumptions. For example, outdoor therapy might not work for a particular client, and worse could be harmful and traumatic, but it still can work equally well to other approaches to psychotherapy. The protective belt consist of our assumptions as to the factors supporting our core assumptions about outdoor therapy.

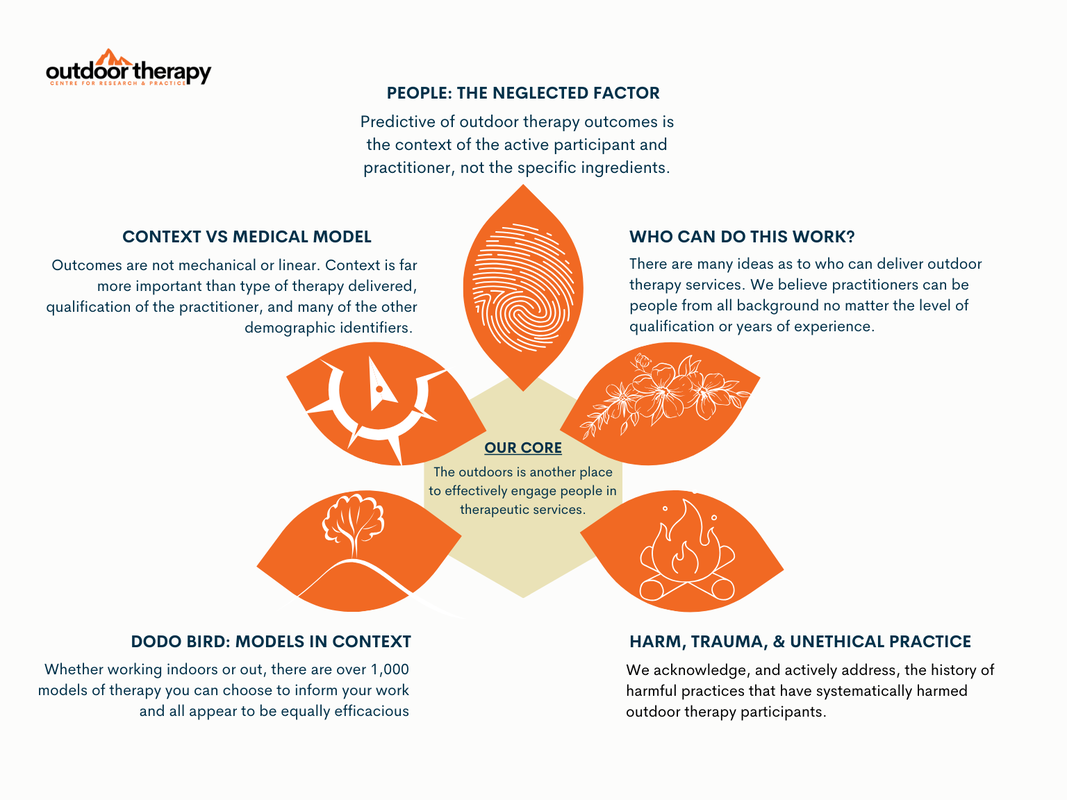

Applying this framework to outdoor therapy, we bring in the following fundamental assumptions:

Our Core:

Our Assumptions:

Any research program can be evaluated based on its ability to generate new knowledge, giving it a progressive trajectory. The progressive nature is determined by the ability to address anomalies (i.e., impacts of unethical practices in outdoor therapy), generate new hypotheses (i.e., exploring why some practitioners are more effective than others), and produce robust research that extends the existing evidence base (i.e., longitudinal data).

Specific to the Outdoor Therapy Centre, our research program involves:

Addressing Anomalies: By focusing on ethics, human rights, and client experiences in outdoor therapy, we explore cases or contexts where outdoor therapy does not produce the expected therapeutic outcomes. We hope deeper our understanding of the conditions under which outdoor therapy is most effective and identify potential limitations or contraindications. By expanding research on the factors predictive of outdoor therapy outcomes, our research helps to protect our core assumptions about the effectiveness of outdoor therapies.

Generating New Hypotheses: Our work aims to explore new concepts and practice frameworks within outdoor therapy to explain underlying pathways for change. For example, investigating the variance in practitioner outcomes, dose effect, therapeutic relationships outdoors, and the development of evidence-informed practitioners can build new knowledge about important factors in outdoor therapy practice.

Robust Research: We hope to conduct rigorous studies to assess the effectiveness of different outdoor therapy interventions and techniques across diverse populations and settings progressing beyond pre/post outcome studies. We intend to examine the long-term effects of outdoor therapy on mental health, well-being, and specific clinical populations. We investigate ethical practice and human rights in the context of outdoor therapy practice.

By following a progressive research program, the Outdoor Therapy Centre hopes to continue evolving and building upon previous knowledge. This approach encourages researchers and those affiliated with the centre to refine and expand their theories, test their hypotheses through empirical research, and contribute to the overall development of evidence-informed approaches to outdoor therapy.

A research program consists of a hard core of fundamental assumptions and a protective belt linking these ideas to the wider world of psychotherapy practice and the helping professionals. These ideas can be modified or abandoned without undermining the core, but adjust themselves to protect the fundamental assumptions. Changes to a protective belt are welcome, and encouraged, but these changes still prevent the falsification of our core assumptions. For example, outdoor therapy might not work for a particular client, and worse could be harmful and traumatic, but it still can work equally well to other approaches to psychotherapy. The protective belt consist of our assumptions as to the factors supporting our core assumptions about outdoor therapy.

Applying this framework to outdoor therapy, we bring in the following fundamental assumptions:

Our Core:

- The fundamental assumption that outdoor therapy can elicit positive therapeutic outcomes for individuals, groups, families, and communities.

- The outdoors can provide a healing environment for enhancing mental, emotional, and physical well-being.

- The outdoors simply provides another avenue for engaging people in therapy who may benefit from therapeutic services.

Our Assumptions:

- Auxiliary hypotheses include specific theories or models of change within outdoor therapy, such as ecotherapy, solution-focused practices, trauma-informed care, or narrative therapy, among many others.

- They also encompass techniques and interventions used within outdoor therapy, such as experiential activities, reflective exercises, group work, adventure-based activities, animal-assisted, or art therapy practices.

- Ongoing research examining the specific outcomes and effectiveness of different outdoor therapy interventions would contribute to how this protective belt support our core, though outdoor therapy practice frameworks should be defined more robustly.

Any research program can be evaluated based on its ability to generate new knowledge, giving it a progressive trajectory. The progressive nature is determined by the ability to address anomalies (i.e., impacts of unethical practices in outdoor therapy), generate new hypotheses (i.e., exploring why some practitioners are more effective than others), and produce robust research that extends the existing evidence base (i.e., longitudinal data).

Specific to the Outdoor Therapy Centre, our research program involves:

Addressing Anomalies: By focusing on ethics, human rights, and client experiences in outdoor therapy, we explore cases or contexts where outdoor therapy does not produce the expected therapeutic outcomes. We hope deeper our understanding of the conditions under which outdoor therapy is most effective and identify potential limitations or contraindications. By expanding research on the factors predictive of outdoor therapy outcomes, our research helps to protect our core assumptions about the effectiveness of outdoor therapies.

Generating New Hypotheses: Our work aims to explore new concepts and practice frameworks within outdoor therapy to explain underlying pathways for change. For example, investigating the variance in practitioner outcomes, dose effect, therapeutic relationships outdoors, and the development of evidence-informed practitioners can build new knowledge about important factors in outdoor therapy practice.

Robust Research: We hope to conduct rigorous studies to assess the effectiveness of different outdoor therapy interventions and techniques across diverse populations and settings progressing beyond pre/post outcome studies. We intend to examine the long-term effects of outdoor therapy on mental health, well-being, and specific clinical populations. We investigate ethical practice and human rights in the context of outdoor therapy practice.

By following a progressive research program, the Outdoor Therapy Centre hopes to continue evolving and building upon previous knowledge. This approach encourages researchers and those affiliated with the centre to refine and expand their theories, test their hypotheses through empirical research, and contribute to the overall development of evidence-informed approaches to outdoor therapy.

Contextual vs Medical Model

The medical model is the dominant discourse in mental and behavioural healthcare. Informed by the work from the International Center for Clinical Excellence, we propose the contextual model of psychotherapy to offer different perspectives on mental health and therapy. As proponents of experiential and contextual views of psychotherapy, we apply this to our research agenda. In the section below, we present the two concepts and describe how these approaches lead to contrasting views of outdoor therapy and research agendas. Both the medical and contextual models of therapy agree that therapy works, indoors and out. Where these models differ is in how they progress from simple understanding of effectiveness.

For example, proponents of the medical model have described the variance across individual practitioner outcomes as a nuisance variable. Simply put, two practitioners delivering the same manualised empirically-support treatment to a similar population of clients will elicit two different sets of outcomes. This finding is replicated across psychotherapy research. Adherence to specific intervention, technique, or model will not be predictive of the practitioner's outcomes. Viewing outdoor therapy through the medical model's lens tends not to progress this research on the field.

Medical Model:

Contextual Model:

While the medical model tends to focus on the biological aspects of mental health and relies heavily on symptom reduction and empirically-supported interventions, the contextual model emphasises the broader context of an individual's life and the reciprocal relationship between the person, practitioner, and their environment. In outdoor therapy, the contextual model is often favoured due to its compatibility with the therapeutic potential of the natural environment and its focus on holistic well-being, personal growth, and interpersonal relationships.

For example, proponents of the medical model have described the variance across individual practitioner outcomes as a nuisance variable. Simply put, two practitioners delivering the same manualised empirically-support treatment to a similar population of clients will elicit two different sets of outcomes. This finding is replicated across psychotherapy research. Adherence to specific intervention, technique, or model will not be predictive of the practitioner's outcomes. Viewing outdoor therapy through the medical model's lens tends not to progress this research on the field.

Medical Model:

- Focus: The medical model views mental health conditions as primarily biological or medical in nature, emphasising the diagnosis, treatment, and symptom reduction of mental illnesses.

- Individual Pathology: It emphasises identifying and diagnosing specific mental disorders based on symptom clusters, often utilising standardised diagnostic criteria (e.g., DSM-5).

- Approach: The medical model relies on specific active ingredients viewed as remedial to the client's mental disorder (i,e, automatic thought records in cognitive behavioural therapy or time in nature for anxiety).

- Outdoor Therapy Integration: In the context of outdoor therapy, the medical model may involve prescribing outdoor activities as adjunctive interventions alongside medication or other medical treatments. For example, nature walks or physical exercise in natural environments may be prescribed as part of an overall treatment plan to complement medication management.

Contextual Model:

- Focus: The contextual model takes a broader view, considering individuals within their social, cultural, and environmental contexts. It emphasises the importance of understanding how environmental factors and social relationships contribute to psychological well-being.

- Interconnectedness: This model recognises the reciprocal influence between individuals and their environments, highlighting how external factors impact an individual's thoughts, feelings, and behaviours.

- Approach: The contextual model views outdoor therapy as simply another way to engage people in therapeutic services that is no more effective than other bona-fide psychotherapy approaches. The client's view of the therapeutic relationship provides far more variance in outcomes as opposed to where the therapy takes place.

- Outdoor Therapy Integration: In the context of outdoor therapy, the contextual model aligns well as it emphasises the therapeutic potential of the natural environment and context of the therapeutic relationships taking place. Outdoor therapy practitioners using the contextual model may focus on facilitating experiences in nature to promote relationship-building, and systematically elicit client feedback to understand more about the client's context.

While the medical model tends to focus on the biological aspects of mental health and relies heavily on symptom reduction and empirically-supported interventions, the contextual model emphasises the broader context of an individual's life and the reciprocal relationship between the person, practitioner, and their environment. In outdoor therapy, the contextual model is often favoured due to its compatibility with the therapeutic potential of the natural environment and its focus on holistic well-being, personal growth, and interpersonal relationships.