On Becoming an Evidence-Based Outdoor Therapy Provider

We live in evidence-based times. Funding and third party reimbursement is often predicated on the type of therapy being provided, which is problematic as this has little to do with the outcome. Evidence-based practice, in our view, is a verb, something practitioners can do unrelated to whether they work indoors or out, and no matter their level of qualification.

According to the American Psychological Association, evidence-based practice is "the integration of the best available research with clinical expertise in the context of patient characteristics, culture and preferences".

Friends of the Outdoor Therapy Centre work to promote contemporary research and inform their practice based on the best available evidence. Based on our contextual model for outdoor therapy, we believe in adjusting and tailoring our outdoor work based on the culture and preferences of those we work with. Achieving recognition of outdoor therapy as "evidence-based" is not a goal post for the centre, it is something practitioners can do every day by implementing evidence-based strategies, such as Feedback-Informed Treatment.

According to the American Psychological Association, evidence-based practice is "the integration of the best available research with clinical expertise in the context of patient characteristics, culture and preferences".

Friends of the Outdoor Therapy Centre work to promote contemporary research and inform their practice based on the best available evidence. Based on our contextual model for outdoor therapy, we believe in adjusting and tailoring our outdoor work based on the culture and preferences of those we work with. Achieving recognition of outdoor therapy as "evidence-based" is not a goal post for the centre, it is something practitioners can do every day by implementing evidence-based strategies, such as Feedback-Informed Treatment.

Outcome Monitoring in Outdoor Therapy

Practice-Oriented Books

How Does Outdoor Therapy Work?

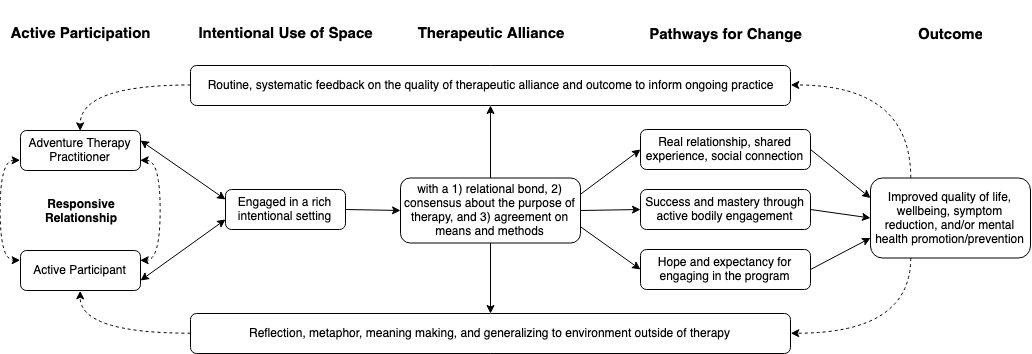

Instead of providing definitive boundaries of what outdoor therapy is or who can provide it, we have provided an illustration capturing our conceptualisation of the pathways of change in outdoor therapy practice. The factors in this are described further in Professor Nevin Harper's and Dr Will Dobud's co-edited book Outdoor Therapies: An Introduction to Practices, Possibilities, and Critical Perspectives. These commonalities are the intentional use of space, active bodily engagement, and a human-nature kinship.

All therapies, whether indoor or out, contain common factors. These are 1) the presence of a helper (therapist/practitioner/facilitator), 2) the person seeking help (client, patient, consumer, etc.), 3) a therapeutic relationship, and 4) a rationale (theory) to inform the 5) methods (activities, techniques) the helper will use. A final common factor is a sense of 6) hope and expectancy that the client is in the right place and likely to experience benefit.

All therapies, whether indoor or out, contain common factors. These are 1) the presence of a helper (therapist/practitioner/facilitator), 2) the person seeking help (client, patient, consumer, etc.), 3) a therapeutic relationship, and 4) a rationale (theory) to inform the 5) methods (activities, techniques) the helper will use. A final common factor is a sense of 6) hope and expectancy that the client is in the right place and likely to experience benefit.

Informed by Wampold and Imel (2015), the above graphic was developed in collaboration by Dobud, Natynczuk, Avota, Pringle, Harper, and Cavanaugh (2023) during the protocol for the Adventure Therapy Outcome Monitoring (ATOM) study. To begin with, we define all people engaging in outdoor therapy as active participants, they are not passive recipients or dependent variables on which the outdoors and therapy act on. Active participants are in a responsive relationship with the outdoor therapy provider, who we refer to as a practitioner. A practitioner is not defined by a minimum qualification, theoretical orientation, level of experience, or any other category.

The practitioner facilitates the outdoor therapy experience in an intentional setting, such as a river to canoe on or a garden to practice horticulture. Some intentional spaces may also be indoors, such as a rock climbing gym. The practitioner and active participant are engaged in a therapeutic relationship, within which is a therapeutic alliance defined by Bordin (1979) as containing 1) a relational bond, 2) an agreed upon reason for being in that relationship (goals, meaning, purpose, best hopes, etc.), and 3) agreement about what the two will do together to achieve the purpose.

Next in the diagram are the pathways for change. Note, we prefer pathways as these are not mechanical or linear factors, they are all contextual. The active participant may experience the relationship with their practitioner or the group they are in to be beneficial. While actively engaging in the outdoors, the participant may experience a sense of mastery which they can apply to their life outside of the therapy. The participant may also experience benefit from feeling a sense of hope that they can overcome problems in their life while engaging in the outdoor therapy.

We prefer to focus on improving wellbeing as opposed to symptom reduction, though both can be important. Based on models of experiential processing, both the practitioner and active participant make meaning from their outdoor therapy experience. The practitioner should use routine, systematic feedback from the active participant to tailor the outdoor therapy based on client outcome and the client's perception of the quality of therapeutic alliance (relationship, goals, methods).

The practitioner facilitates the outdoor therapy experience in an intentional setting, such as a river to canoe on or a garden to practice horticulture. Some intentional spaces may also be indoors, such as a rock climbing gym. The practitioner and active participant are engaged in a therapeutic relationship, within which is a therapeutic alliance defined by Bordin (1979) as containing 1) a relational bond, 2) an agreed upon reason for being in that relationship (goals, meaning, purpose, best hopes, etc.), and 3) agreement about what the two will do together to achieve the purpose.

Next in the diagram are the pathways for change. Note, we prefer pathways as these are not mechanical or linear factors, they are all contextual. The active participant may experience the relationship with their practitioner or the group they are in to be beneficial. While actively engaging in the outdoors, the participant may experience a sense of mastery which they can apply to their life outside of the therapy. The participant may also experience benefit from feeling a sense of hope that they can overcome problems in their life while engaging in the outdoor therapy.

We prefer to focus on improving wellbeing as opposed to symptom reduction, though both can be important. Based on models of experiential processing, both the practitioner and active participant make meaning from their outdoor therapy experience. The practitioner should use routine, systematic feedback from the active participant to tailor the outdoor therapy based on client outcome and the client's perception of the quality of therapeutic alliance (relationship, goals, methods).